The lanky red-headed museum guide perked up when we asked him about the book he was reading. He sat behind the desk at Iceland’s Reykjavik Settlement 871 Museum, an underground den that displayed the site of a ruin dug up from under a street in the city. It’s not what I’m used to in terms of ruins, by which I mean they’re not Greek ruins, which jut up everywhere—on the subway, next to beaches, marble sparkling in the sun.

I find it hard to believe that anyone has lived on this desolate Scandinavian rock for centuries. And yet, they have, since around 800. The museum showed us pictures of the huts people used to live in. The wind was so strong outside the hotel we were staying in that I was scared the window would cave in the night before. Those must have been stubborn huts.

The guide, let’s call him Lars, was reading an ancient book of spells. “Folklore is kind of my thing,” he said.

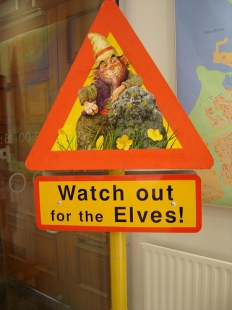

This reminded me of a fact I’d read on the airplane: apparently, half of Iceland’s population believes in elves. This seemed a statistic too wonderful to be real. I’d once heard Irish people were so superstitious about fairies they wouldn’t discuss them. I wanted to see if I got the same spine-shivering reaction from my intellectual friend with the man-bun.

He rolled his eyes, as if this was a question he was born to negate.

“That’s ridiculous,” he quipped. “Anyway, they’re not elves. They’re hidden people. They’re tall, with red hair, actually.”

Then I look at him. He fits the bill: tall, with red hair. I had to ask.

“Are you a hidden person?” My family looked at me with horror, and also amusement. They were happy someone asked the obvious question.

“No,” he said, after a pause, “You wouldn’t be able to see me if I was.”

Bummed that I missed an opportunity to see my very first Hidden Person, he continued to tell us about “his thing:” folklore. He was reading an old sorcery manual, with runes and recipes on each page.

Judging by my time in Iceland, if I lived there, these are things I would wish for with a book of spells: cheaper wine, the sun to poke through the clouds occasionally, weather that didn’t vacillate between hail and sun every twenty minutes, for fewer consecutive consonants in my words.

could they be real?

The museum was pretty quiet, so Lars the Hidden Person took us on his own tour. It must get quiet, sitting behind a desk, selling museum tickets to Americans who usually don’t think to ask about hidden people and where to buy ingredients for spells.

Apparently, if we were to trust him, the Icelandic language has barely changed since it was first written down in the 11th century. Some Norse people stepped foot on Iceland and started writing things down—epic poems, laws, and town directories. With each word, they were cementing the language that Lars would speak on dates with his Icelandic girlfriend, say.

“Let’s say I met someone from this exhibit,” he said. I’m sure he’s fantasized about this many-a-time. “We could, quite easily, have a conversation together.”

“Iceland has been free from outside influence for so long that our language remains the same.” They’re also obsessed with keeping the language pure, and come up with Icelandic words when most languages just incorporate foreign elements. Instead of letting loanwords muddle up their tongues, the Icelanders invent words with Old Norse roots. Though their old settler counterparts may not be able to understand what a telephone is, the word telephone will be discernible, not something vaguely Latin or English.

The longest word in Icelandic is “Vaðlaheiðarvegavinnuverkfærageymsluskúraútidyralyklakippuhringur,” which translates to, “Key ring of the key chain of the outer door to the storage tool shed of the road workers on the Vaðlaheiði plateau.” I’m not making this up.

In addition to having pride in their language, the tour guide goes on to tell us about language education in Iceland. I’m happy he’s addressing this, because his English is so good it’s making me self-conscious. It’s at the point where I’m fairly sure his English is better than mine. Icelandic students also learn Danish, English, French and German. I think back to my Spanish class, in which the curriculum consisted in learning recipes for Mexican food, and grin nostalgically at the state of American language education.

Since Iceland is essentially a volcanic rock in the middle of the Atlantic, they’re able to keep piling up their language with purisms. I comfort myself that though the Greeks can’t run museums as well as the Icelanders, as my mother keeps shouting enthusiastically throughout our time at the museum, and though I can’t converse with Geoffrey Chaucer, I do have something.

This is the point in the essay when I should come up with something that I, as an American, have, that redeems my American nationality. Yes, we have some hotter weather, and yes, perhaps more skyscrapers. But judging by my time in Iceland, they have a lovely quality of life, an abundance of outdoor heated swimming pools, and limitless electricity and hot water. They may or may not have hidden people. They can practically have conversations with ancient ancestors, and if anyone has their things together enough to make a time machine, it’s the Icelanders.

We leave Lars and the museum a bit shaken up, and I for one hope he doesn’t cast any spells on us on our way out.