Title: My Sister, the Serial Killer

Title: My Sister, the Serial Killer

Author: Oyinkan Braithwaite

Genre: Feminist satirical slasher (perhaps the best niche genre)

Describe it in a sentence: A Nigerian woman’s extremely beautiful younger sister lures men into her web then slaughters them, leaving the woman to clean up her messes.

TV/movie character who would like it: Oh, this one is easy – the women in Killing Eve would eat this book UP. Eve probably reads serial killer fiction just for fun, because she’s an obsessive person and can’t leave work at home. Villanelle probably read the book and smirked at Ayoola’s sloppiness. Amateur.

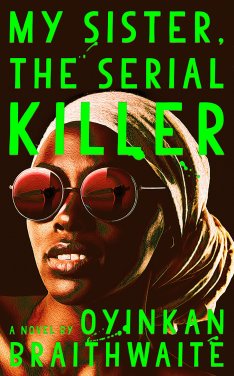

I’ll admit it. I was compelled to read My Sister, the Serial Killer entirely because of the title and the cover. Clearly, the individuals at Doubleday marketing this book knew how to draw me, a millennial 20-something, into its pages. That girl! She just IS the epitome of cool. She looks at a nearby act of violence with an unreadable Mona Lisa smile. Whereas I would be screaming and calling for the police/Oprah to save me, she seems confident that she’ll be all right. How come? And then the title! Her sister — the serial killer? What! Clearly, the narrator has either an obsession or a reluctant amount of affection for her sister. I needed to know more.

The novel is structured around one hell of a conundrum. Korede is a Nigerian woman whose life has been defined by responsibility. She’s a nurse. She’s always doing the right thing. She’s meticulous AF. All of these traits come in handy when it comes to cleaning up her younger sister Ayoola’s messes, of which there are many. Ayoola is strikingly beautiful, frivolous, lacking in foresight — and in empathy. She gets a TON of attention from men and has grown to loathe them for it. It seems like Ayoola thinks of men as pitiable cockroaches not in control of their instincts. She has to kill them. Normally, Korede is able to separate herself from Ayoola’s victims. Then, Ayoola starts sidling up to a doctor at Korede’s hospital — and suddenly, Korede’s conscious is flaring up. Can she let Ayoola rack up another victim? Korede’s split between loyalties and laws.

Obviously, there’s a rational way to refute the entire premise of this book. Many of you might be thinking, Korede’s crazy! Why is she protecting her serial killer sister?! That is a good question. Obviously, Braithwaite comes up with a plot device that sort of explains it. But it’s never wholly explained. Korede often wants to sabotage her sister. She wants to sell her out. Ultimately, I liked how open-ended and morally ambiguous all the characters are. Here’s a woman who abides by the rules in every way, then uses that instinct to create a system of rules that protects her own rule-breaking sister — just because she loves her sister more than she loves a corrupt, patriarchal society. Humph!! *insert thoughtful emoji here.*

My Sister, the Serial Killer falls squarely into the category of Cathartic Reads. If you’re a woman in America today, you might be turning to food, reality TV, foot massages, long baths, or shutting off all electronics for the duration of the weekend in order to cope with the sad fact that many men do not care about your pain. For some reason, this week, more than many that have come before in the duration of the MeToo movement, has sent me hurtling back into past relationships with men. I’ve been rereading minor instances of dismissal and condescension for what they are — symptoms of an ingrained lack of regard for my experiences and expertise when it came to verbalizing that experience. Ayoola dealt with this in her own way.

This is a book about female rage, about revenge, about sticking it to the man (literally). It’s also about the knottiness of sisterhood, those knots that are tied just by the fact that you grow up in the same circumstances and thus will be bound to each other forever. Even if Korede turned Ayoola in, she’d still be her sister. She’d be the sister who betrayed her own sister. (For a book about siblings betraying other siblings, check out Astrid Holleeder’s electrifying memoir Judas, about her decision to testify against her crime lord brother.).

My Sister, the Serial Killer book balances gory plot with thoughtful implications. If only ALL books could be this fun and this thought-provoking!